Interview with Oluseun Taiwo (Solideon)

Echoes of Future Matter — Interview with Oluseun Taiwo (Solideon)

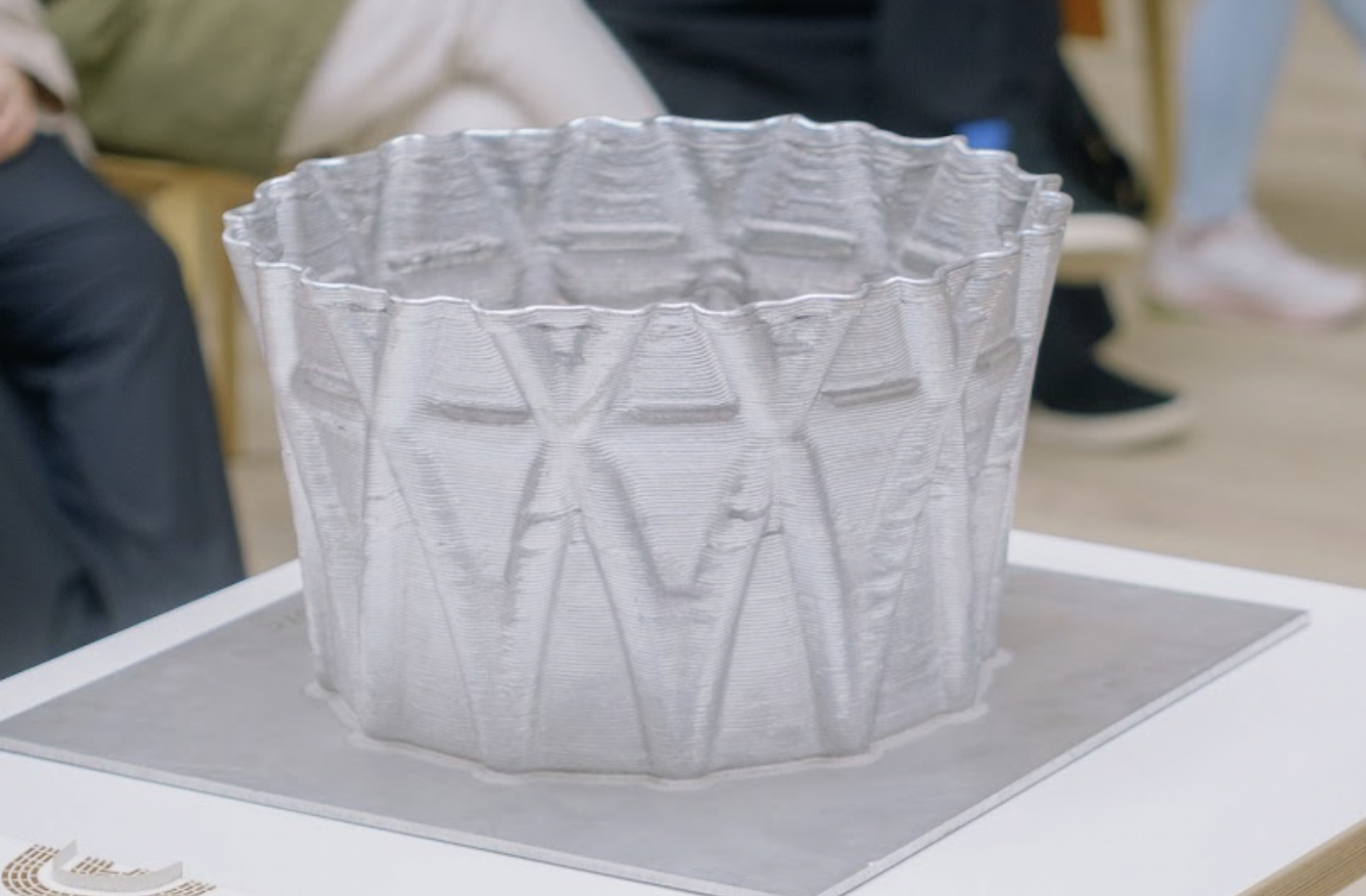

In this interview, Oluseun Taiwo explains how steel shapes his design thinking, how human expertise and automation interact, and why imperfection is essential for robotic learning. He describes how collaboration with architects accelerated innovation at Solideon, including their bio-inspired 3D-printed underwater vessel.

Alexey: What material, if any, has shaped the way you think about form or space — and why?

Olu: You know, I think steel recently has done so. Mainly because I look at the supply chain of

where it comes from, and it’s something that everyone in every industry needs—from

building to maritime to aerospace. That’s serious.

The more you can, if you have to use that material, being able to redesign things

lightweight and ergonomic—not just for performance, but from a cost

perspective—that’s huge. So steel, just because we have a lot going on with it right now,

has probably shaped my thinking about space.

Alexey: Where do you feel the line blurs between human touch and machine logic in your work? Where should humans intervene in automated processes?

Olu: I love that question. Right now, humans handle the workflows: a part comes in, they send it to a robot, do basic coding, and generate a toolpath in our software. Then the robot prints. As it prints, it has feedback loops that let it self-correct—and it remembers those corrections. Each time we print, we get better because the system learns, not just the operators. That’s where human touch shifts into machine automation. The next step: software will start writing toolpaths itself, based on that memory. You want robot speed, not dependence on one or two human experts. Humans, instead, should focus on making sense of the data and noise—that’s where our value is.

Andrei: And where should humans intervene? Is it at the stage where robots become like ‘digital gardeners,’ tending natural processes? Or somewhere else?

Olu:I still think humans are critical in material science. There isn’t a database yet that replaces a metallurgist’s judgment—cutting open metal, making interpretations, deciding what’s acceptable. Doing that live during manufacturing is borderline impossible today. So humans will remain deeply involved in that. It’s also where customers like the Navy and Air Force spend the most money—they’re most concerned about that part.Think of it like Westworld: first, the robot is programmed to play the piano, then it learns to play on its own. That’s the slingshot effect we want—robots generating and editing toolpaths—but material science is still the biggest barrier.

Andrei: Are you open to imperfection—open to surprising things emerging from the process?

Olu: Yes, a thousand percent. Imperfections are how we test. If everything is perfect the first time, we didn’t learn the bounds. We try to fail fast, cheaply. Sometimes we purposely feed the robots bad code or bad conditions, to see how far we can push limits. Then we validate that with material testing.Imperfections are how you get a robotic process—‘inhuman’ by nature—to start looking like a human process. You don’t want robots to build like robots; you want them to build like humans. That only comes through learning and imperfection.

Andrei: How has collaboration with other artists and firms been importantin your work? Have you ever been surprised?

Olu: Yes. Two of my most senior engineers actually have architecture and industrial design degrees. Our VCs were shocked—‘Don’t you need a SpaceX guy?’—but it turned out the tools architects use were exactly what we needed.We built our first software breadboards using Rhino and Grasshopper. Everyone in your field uses it, and translating it into aerospace saved us millions of dollars and 6–12 months of time.That was a big surprise—how quickly we could move by learning from architecture and design.

Andrei: Exactly—tools like Rhino, scripting, Grasshopper are open, adaptable, and rigorous. You can design, generate G-code, connect to machines—all things your company needs.

Olu: Exactly. That’s what bridged art with science for us.

Alexey: What does Echoes of Future Matter mean to you—personally or poetically?

Olu: For me, it’s the non-competitive exchange of ideas. On the panel, everyone came from different viewpoints, but all were working on world-changing projects—and willing to share knowledge openly. That’s rare, and it’s invaluable when you’re building. It reminded me: I’m not special—others are solving the same problems differently. That’s good. It opened my mind about who we should hire and how we should design. Honestly, it was one of the most value-added things I’ve done this year.

Andrei: So you loved the multiplicity of voices, the echoes—not just one teacher, but a collective.”

Olu: Exactly.

Andrei: How can we achieve poetic expression through computational design methods?

Olu: By showing it physically. For example, our new UUV concept—a fully 3D-printed undersea vessel. Computational design made it:60% lighter than conventional / Integrated ballast tanks / Built in 4000-series aluminum (cheap, repeatable) / Looks like a squid. It shows how we can rethink a pressure vessel: not one precious artifact, but a fleet of affordable, iterative prototypes. That’s poetic expression—taking ideas that might look crazy, and making them real.

Andrei: It’s poetic and sea-creature-like. You’re breeding a fleet of autonomous vessels that evolve computationally.

Andrei: How do we bridge the gap between high-tech fabrication and artisanal knowledge?

Olu: By doing exactly what you did at this event: create a safe forum where people share openly. Normally in high-tech, everyone keeps trade secrets. But when everyone contributed equally, the bridge appeared. I felt safe to share. Others did too. That’s how artisans and engineers actually connect.

Andrei: So you felt that bridge was established—that artisans and high-tech met in the middle.”

Olu: Yes, exactly.

Andrei: How can we work meaningfully with local context, materials, and cultures? How can we integrate biodegradable, transparent, compostable materials?

Olu: It comes down to involving local people. Don’t just build in a vacuum—hire them, bring them into design reviews. As for biodegradable and compostable materials: honestly, people won’t do it unless they’re forced to. Human nature chooses what’s easy now, not what helps in 20 years. Change will require policy pressure and cultural demand.

Andrei: Yes, that was one of the most memorable panel moments—bringing context and culture back into design.

Olu: Exactly.

Alexey: Where do digital processes intersect with organic, living systems?

Olu: I see it most in the oceans. Ships, submarines, and now autonomous vessels constantly interact with one of Earth’s richest ecosystems. Hull design, wake behavior, even bio-inspired forms—like submarines shaped like manta rays—all show how digital processes directly shape biodiversity. We don’t talk enough about how maritime tech impacts life under the surface. But it’s huge.